Can India’s ancient desert water system survive modernity?

Can an ancient water system in India’s Thar Desert survive modern pressures? Discover the khadeen in Bada Bagh's fight for a sustainable future.

Deep in the Thar Desert lies Bada Bagh — the “big garden” — where an ancient water system has sustained farming for centuries. Can it survive the market age?

Bada Bagh — which means “big garden” — is a green valley tucked into the dunes of Rajasthan’s Thar Desert in north-western India. Near the city of Jaisalmer, its orchards flourish thanks to a five-hundred-year-old water-harvesting system known as khadeen. In this arid region, where water is scarce and rainfall erratic, the khadeen has made cultivation possible for generations.

After India’s Independence and the abolition of royal titles, the Girdhar Smarak Dharmarth Nyas Trust took charge of the former royal family’s properties, including Bada Bagh’s khadeen and other traditional water structures. Today, however, this delicate system faces mounting pressure from expanding mining, tourism and commercial water sales. Understanding the khadeen is vital not only as heritage, but as a living example of desert resilience.

Cultivating the bed of a seasonal lake

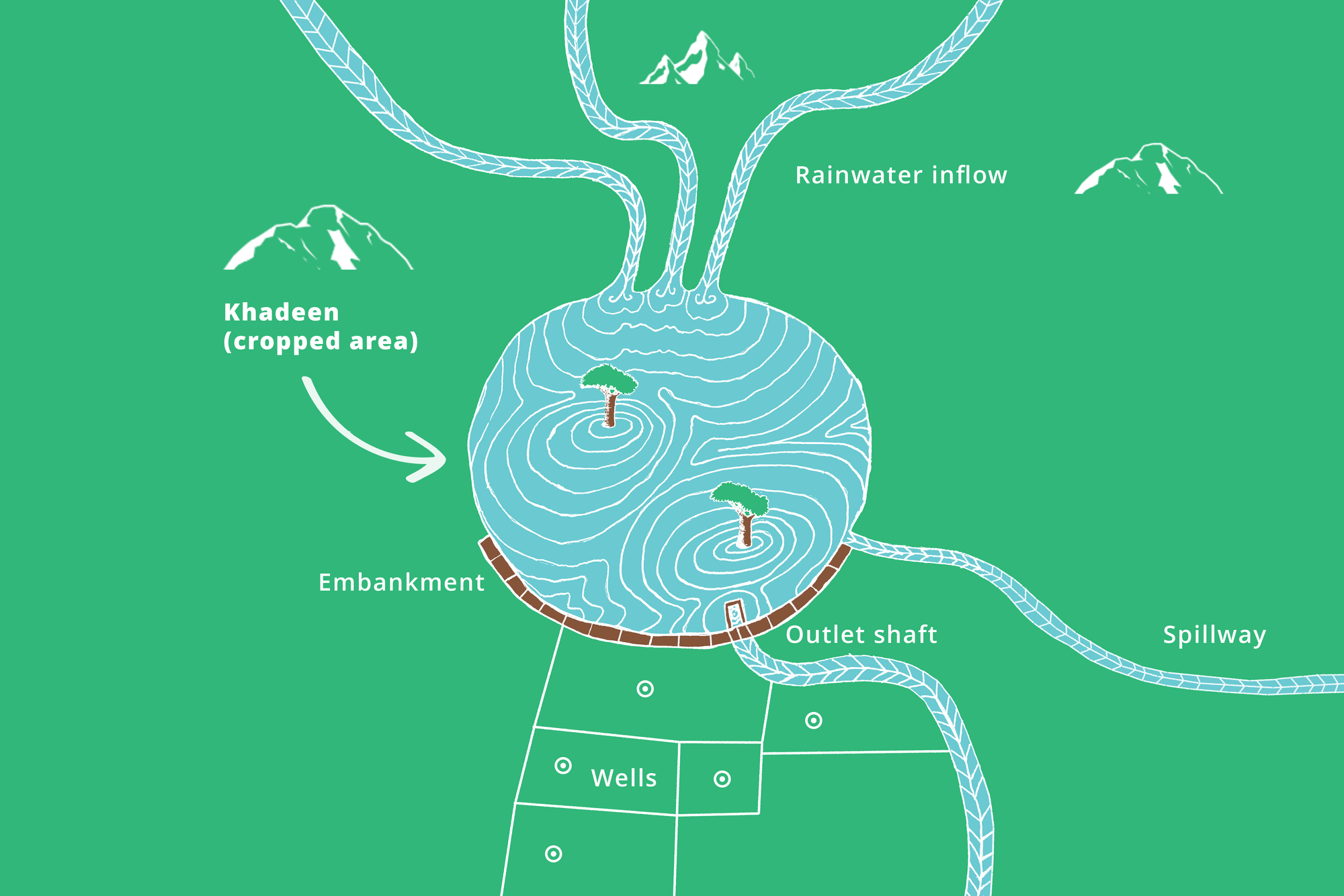

During the monsoon months of July to September, the stone embankment of the khadeen captures seasonal runoff and forms a temporary lake across the valley floor. Around the Hindu festival of Raksha Bandhan in August, farmers gather to assess the water level and decide which crops to sow.

“If the rainfall is abundant, we plant wheat, mustard and chickpeas,” says one farmer. “Otherwise, we grow only chickpeas.”

On the same day, the descendants of Jaisalmer’s former rulers — locally called the darbar — announce an annual tender granting the right to cultivate the lakebed. The highest bidder also gains permission to sell water from a narrow well downstream of the embankment.

By October, once the lake is drained through a central shaft, the saturated soil is ready for winter crops. The moisture stored beneath the surface sustains plants from October to March without any irrigation. Like most khadeens, Bada Bagh lies above an impermeable rock layer, forming what hydrogeologists call a “perched aquifer”. In simple terms, this prevents fresh water from mixing with the deeper saline groundwater below.

Left: The drainage canal in Bada Bagh. Right: Diesel motors are used to lift water from wells, though traditional lifting using animals is also practiced. Photos: Pierantonio La Vena

Irrigating the downstream orchards

Below the embankment, a chain of orchards — or wadi — stretches along the valley. Here, vegetables, fruit and grains grow with help from narrow wells called beriyaa. While the khadeen fields depend on stored soil moisture, water from these wells irrigates the wadi using diesel pumps — though a few families still lift water in leather bags by animal power. Yields vary sharply from one well to another, depending on depth and position.

The darbar owns the largest orchard, shaded by century-old mango trees and alive with peacocks. Community members help maintain it, as it lies closest to the embankment and benefits from the first outflow of lake water.

Left: A leather bag – known as chara locally – used in traditional lift irrigation hangs from a tree. Right: The khadeen’s embankment in Bada Bagh in the Thar Desert. Photos: Pierantonio La Vena

Pressures on the system and communities

Most work connected to the khadeen is carried out by villagers on the valley’s edge, mainly from the Mali caste — traditional gardeners and orchard-keepers. New road construction cuts through catchment areas, reducing natural runoff. Rising demand for groundwater, fuelled by tourism and land fragmentation, has caused both ecological stress and social unease.

“When roads block the streams, the lake fills less,” says one villager. “And when tankers take our water, the wells fall.”

Water access also shapes local power. Although decisions should be made collectively, those with the most productive wells hold greater sway. Some farmers, under pressure from the market, sell water to nearby hotels for a steady profit. Others refuse, preferring to reinvest water in their orchards. The trade-off is stark: short-term income versus the long-term health of the shared aquifer.

As the water market grows, poorer cultivators risk exclusion — first from decision-making, then from irrigated land itself. A system once built on cooperation is slowly shifting towards competition.

Impact of shift from tradition

For centuries, khadeen land was cultivated under sharecropping: farmers kept two-thirds of the harvest and gave the rest to the darbar. The newer tender system replaces this with upfront cash payment. For the 2023–2024 season, the winning bid reached INR 6 lakh (about EUR 6,800). This shift has priced out many locals and weakened the social fabric linking the lakebed and the orchards below.

The change also affects seed choices. “Earlier we saved khadeen seeds,” says the current contractor. “Now we buy from the market — we can’t risk saving seed if we lose the tender next year.”

The khadeen’s fertile silt still supports organic farming, but downstream orchards increasingly rely on chemical fertilisers. As a result, yields rise but quality drops — and so does the market value of their produce.

A fragile balance

Bada Bagh now stands at a crossroads, balancing tradition and modernity. The ancient khadeen remains an ingenious answer to scarcity, but its survival depends on social agreements as much as on stones and slopes.

Sustaining this desert oasis will mean reviving community management, regulating groundwater use and recognising the khadeen as a living heritage landscape. Its endurance would show that progress need not erase the past — that even in the driest desert, cooperation can still make things grow.

Enjoyed this issue? Please share it with a friend or reply to this email. I’d love to hear your thoughts! 👻

Discover the Mekong. Meet the unforgettable people of Vietnam’s Delta. Watch my film here.

Let’s connect! Find me on LinkedIn and Bluesky for quick thoughts. For a deeper dive, visit joepjanssen.com.